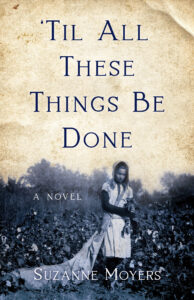

When her beloved father mysteriously vanishes, sixteen-year-old Leola Rideout has little time to question why. With the 1918 influenza epidemic in its second year, social turmoil raging across Texas, and poverty a constant threat, it’s all she can do to keep her young sisters–and dreams–alive. Only when Papa returns in haunting visions decades later does Leola finally confront this loss, leading to a remarkable family discovery that could bring the peace she seeks.

I caught up with Suzanne Moyers today on Book Club Babble to learn about her inspiration for writing this story and much more. Thank you for chatting today, Suzanne!

Tabitha Lord: How did you come up with the idea for this story?

Suzanne Moyers: I was sixteen when I first witnessed my grandmother, Nana, crying out to the ghost of her long-lost father. She was in the early stages of dementia but these Ghost Papa episodes, as I called them, left a deep impression, driving me to find out more about this mysterious chapter of our family history. It had all the seeds of a compelling narrative: rich historical setting, stalwart heroine, the quest to understand a betrayal. I’ve always been a curious person and this subject touched a deep place in my heart, motivating me through the tough journey of bringing a novel to fruition.

early stages of dementia but these Ghost Papa episodes, as I called them, left a deep impression, driving me to find out more about this mysterious chapter of our family history. It had all the seeds of a compelling narrative: rich historical setting, stalwart heroine, the quest to understand a betrayal. I’ve always been a curious person and this subject touched a deep place in my heart, motivating me through the tough journey of bringing a novel to fruition.

TL: The 1918-21 influenza epidemic plays a crucial role in the story. How did your experience of the ongoing COVID pandemic affect the writing of these scenes?

SM: I wrote the chapters involving the ‘great influenza’ (once known as the Spanish influenza) long before the COVID pandemic, based mostly on research and my grandmother’s recollections. It was eerie, revisiting those scenes from the vantage point of this latest epidemic. Though the historical details remained the same, my first-hand experience of COVID gave me an emotional perspective I drew on when revising that part of the book. In fact, I came down with the virus while editing final proofs of the novel. It felt extra-surreal, reading those passages while coughing and feverish.

TL: What were the differences or similarities, if any, between the two epidemics?

SM: There were some obvious differences. The influenza pandemic struck before the advent of modern medicine, when people were just beginning to understand how simple measures like handwashing could prevent the spread of disease. Though herbal remedies, like the asafetida root used by the novel’s Black healer, Nancy Gumbs, did help with certain symptoms, there were no effective treatments for dangerous side effects of the virus—and certainly no vaccine.

The influenza pandemic also happened when America was largely rural, and communication methods were still primitive, so it was difficult to broadcast the kind of public health information that might have saved more lives. During this recent pandemic, it was just the opposite—in fact, at one point during COVID, I had to manage my news intake or risk being crippled by anxiety.

Interestingly, both epidemics happened during periods of rising xenophobia and racism, sowing the seeds for conspiracy theories and the scapegoating of immigrants and ‘non-white’ Americans. I was surprised to discover that both pandemics gave birth to similar social movements advocating for racial and gender equality, workers’ rights, and educational reform. It’s like the prospect of such an imminent threat to mortality makes people realize they don’t want to wait anymore for change that is long overdue.

TL: Speaking of social justice: Much of the story takes place in Texas during the early 1900s, at the height of ‘Jim Crow’ oppression, and you don’t shy away from including that reality as an important part of the setting. Did you worry these details would distract from the novel’s central plot?

SM: In early versions of the novel, I made passing references to the bigotry and racism of the time (which, by the way, was rampant not only in Texas and other parts of the south but across the country). As I dug deeper into my research, however, I realized white supremacy would’ve played a daily, insistent role in the lives of all my characters, that it was woven through the fabric of every social interaction. Writing from the perspective of a white protagonist, I imagined being marinated in that toxic culture from the hour of your birth and how conflicted a perceptive adolescent like Leola would’ve felt by the flagrant hypocrisy of her Protestant, Do Unto Others culture. While someone of her gender, age, and economic status would never have played the white savior, when Leola witnesses a Black childhood friend risking his life to speak out against racism, it does inspire her own voice of protest—however small and halting.

TL: You’ve said that the novel’s fictional conclusion was inspired by a real-life twist in the case of your missing great-grandfather, the model for “Papa”. Without giving too much away, can you tell us more about that?

SM: Over the years, new facts emerged suggesting Papa didn’t leave home of his own volition. Yet there was still this question of why he hadn’t reclaimed his children when he knew they were in dire straits. Then, not long after my grandmother started experiencing those Ghost Papa episodes, we discovered a strange coincidence that, in my mind at least, hinted at a possible answer to this question. For a long time, that possibility worked its way through my imagination, eventually seeding the closure my grandmother never had but that I like to believe could be true.

Suzanne Moyers, a former teacher, was an education editor and writer for over 20 years. A lifelong history geek, Suzanne spends her free time as a volunteer archeologist, mudlarker, and metal detectorist. Suzanne is the proud mom to two amazing young adults, Sara and Jassi, and resides in the greater New York City area with her husband, Edward, and spoiled fur baby, Tuxi. You can learn more about Suzanne on her website.

Suzanne Moyers, a former teacher, was an education editor and writer for over 20 years. A lifelong history geek, Suzanne spends her free time as a volunteer archeologist, mudlarker, and metal detectorist. Suzanne is the proud mom to two amazing young adults, Sara and Jassi, and resides in the greater New York City area with her husband, Edward, and spoiled fur baby, Tuxi. You can learn more about Suzanne on her website.