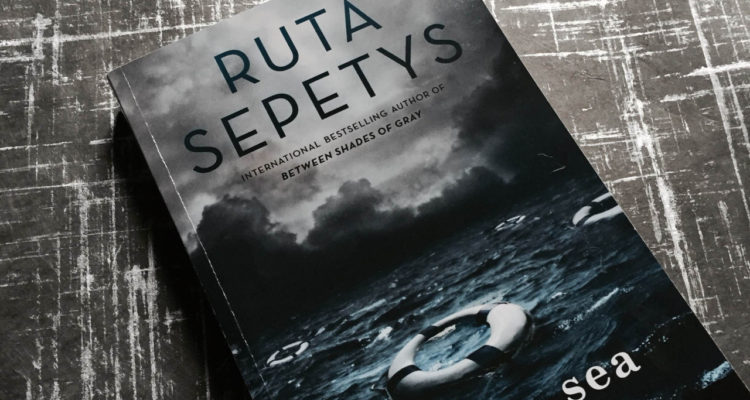

Both of my grandpas served in World War II. One was a Navy man haunted by his time in the Pacific; the other talked of his glory days flying bombers in Europe until the day he died. For me, World War II was part of family history. But for many of today’s young adults, their awareness of the war comes from history books, a chapter or two devoted to disembodied facts and figures. Author Ruta Sepetys changes all of that with her latest historical YA novel, Salt to the Sea (released February 2016).

The book is about a ragtag group of multinational children and teens desperately trying to flee East Prussia before the Soviet advance. It’s 1945 and Germany and its territories are rapidly falling, but still the Third Reich hasn’t given official evacuation orders to the people living in its borders. Sepetys’ characters by chance find each other on the long trek to the port of (what is today) Gdynia, Poland. They are seeking passage aboard a ship bound for anywhere else. They each have secrets; they all have burdens.

There’s Joanna, the bright, beautiful Lithuanian nurse and Florian, a mysterious able-bodied German not in uniform yet on a supposedly top secret mission. They are accompanied by Emilia the pregnant Polish girl, an orphaned six-year-old boy, and an old shoe maker. They are starving, exhausted, and crossing a frozen landscape in January by foot. Each night they must find shelter from the elements and avoid both Nazi and Soviet soldiers who prowl the countryside.

After an onerous journey, they finally make it to the port. It’s overrun with a crush of desperate humanity trying to escape Allied bombs and the indiscriminate rape and murder perpetrated by the Red Army. Boats built for fewer than 2,000 passengers take on 10,000 souls, as was the case of the MV Wilhelm Gustloff, the doomed ship our refugees eventually gain passage aboard. Soon after disembarking, the boat is hit by three Russian missiles. It sinks in about 45 minutes. Over 9,000 people are lost, including as many as 5,000 children.

Sepetys deft writing made reading this novel a stomach churning experience. She describes the bodies of dead children bobbing in the waves and banging against lifeboats, their little feet in the air as their heavy heads sink beneath their life vests. She talks about the mother wailing that her infant’s wet diaper has frozen to the baby, and will she be able to get it off without tearing the child’s skin? Sepetys tells of the orphan boy who takes a one-eared stuffed rabbit as a toy. The bunny was abandoned after its young owner was shot dead in his own bed.

The reader follows the heartbreaking stories of these juveniles who are beaten, raped, frozen, starved, and sunk in the Balkan Sea. The tragedy she relays is visceral because the narrative alternates every fourth chapter with the point-of-view of another teen struggling to survive. I had to put the book down at times, especially while reading it as my own young son played nearby. The scale of the crisis was personalized in this novel—the intrinsic decency of most of the characters making what happened to them even sadder.

Sepetys was inspired to write the story after discovering that the sinking of the MV Wilhelm Gustloff, the worst maritime disaster in history (with casualties far exceeding that of the Titanic), was little-known. The Nazis were still sending propaganda to its provinces, claiming imminent victory, so publicizing this event would have been counterproductive. The author’s own distant cousin narrowly avoided being a victim of this sinking. She held a ticket for the Gustloff, but at the last minute missed boarding and took another ship.

This book reminded me that wartime heartbreak isn’t one-sided: not everyone living under Nazi occupation was also a Nazi. Furthermore, one can’t help but draw parallels to today’s Syrian refugee crisis, the greatest since World War II. The desperation, opportunism, and deflation of civility described in this novel cannot be unique to World War II. Finally, stories like this always make me wonder if I’d have the grit to survive such a calamity all the while I pray to never find out.

This novel is dark, but so can be life, especially for those born into unfortunate times and places. Although it does end with a silver lining for some characters, this war was brutal—a fact Sepetys illustrates sometimes all too clearly. She is a spare and effective writer, a trait carried over from her other books, such as Out of the Easy, another historical YA that I enjoyed immensely. Salt to the Sea is well-written, but sometimes hard to endure, as I wished for reprieve for these characters that did not come, the tragedy worse for knowing it really happened.

Q: What did you think of this book or this author’s other novels? Do you have a favorite?