To the Woman in the Coffee Line,

I wish that I had learned your name.

You inspired me – first to pity, for your story was so very sad, and then to tribute because you were so loving and so brave.

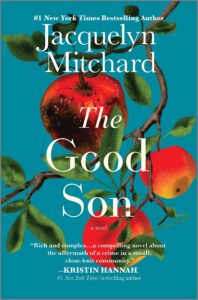

I wish I knew your name because the story of my new novel, The Good Son, is, in part, your story. It’s your story only in part, and this is important because I used the author’s privilege in a way that I hope you would approve of.

You dropped your book, and I picked it up. We were in a big hotel where a nationwide writer’s association was hosting a large conference. There were hundreds of writers in attendance and I was to give the keynote address. After I got ready, I ran downstairs to treat myself to a latte, and, just by chance, I was standing behind you in the line. After I handed you your book, I asked if you were there for the conference. No, you said, you came every week to this hotel, some distance from your home because it was near the prison where your son was – and would be, for a substantial number of years.

No, I thought then, selfishly, no, don’t tell me why he’s there … but you did.

Your son had murdered the only girl he ever loved while he was so messed up on drugs that he had no memory of the crime. Then you told me something that changed the nature of the tale from something that was only sordid and heartbreaking to something transcendent: One day, you said, you went to the cemetery to place white roses (the girl’s favorite) on her grave. Suddenly, the girl’s mother showed up. You were terrified: What would happen? Would the girl’s mother hit you? No matter what she did, you decided you would stand and take it. You deserved it. But the girl’s mother held out her arms and the two of you clung together and sobbed. “At least,” said the girl’s mother, “You can still touch him.”

you told me something that changed the nature of the tale from something that was only sordid and heartbreaking to something transcendent: One day, you said, you went to the cemetery to place white roses (the girl’s favorite) on her grave. Suddenly, the girl’s mother showed up. You were terrified: What would happen? Would the girl’s mother hit you? No matter what she did, you decided you would stand and take it. You deserved it. But the girl’s mother held out her arms and the two of you clung together and sobbed. “At least,” said the girl’s mother, “You can still touch him.”

Needless to say, when I gave my talk fifteen minutes later, I had to summon the angels of past experience to guide me through on muscle memory – and I still have no memory of what I said that day or whether the audience liked it or what happened next.

All I could think of was you.

All I could think of was how grateful I was not to be you … or the other mother … and how I wished I could offer you comfort and the assurance that this was not your fault.

I never saw you again. I never knew your name.

But I never forgot you.

Several times, I told your story to my agent and said I wanted to write a book based on those events. “That’s all interesting and compelling,” he said. “But there is no way that you could make any of those characters sympathetic.”

Finally, after a book I was writing fell apart, I insisted that he let me at least have a try. If he was not on board after a chapter, I would give it up. When he read what I wrote, he was on board, and then the task was to find a publisher willing to take a chance on such a sad story.

But, an author is like a goddess in a little space: I can do what I like with real events. I can toss them up into the air and spin and catch them and cover them with soot or stardust.

That’s what I did. I changed things for you … to the degree possible, I unbroke your broken heart and gave you, at least, some hope.

Eight years have gone by. You are out there somewhere, under this same sky, probably going each weekend to that same hotel, unless your son has been transferred to another prison. I’ve even been back there. But you’re the human equivalent of a haystack needle. Would I even know you if I saw you again?

Now, I wish I could give you this book. But you don’t even know I exist. Still, we are mothers together and, though I can never share your experience – at least I hope I never will – I know that your grief must be a bottomless pool you can climb out of only in your deepest dreams.

Later, when I asked my agent how he thought I had managed it, he said it was because I love my characters and I want readers to love them too. That’s true. I do. Mother and stranger, I love you as well.

Yours, Jackie M.

Jacquelyn Mitchard was born in Chicago. Her first novel, The Deep End of the Ocean, was published in 1996, becoming the first selection of the Oprah Winfrey Book Club and a #1 New York Times bestseller. Nine other novels, four children’s books, and six young adult novels followed, including Two if By Sea, No Time to Wave Goodbye, Still Summer, All We Know of Heaven, and The Breakdown Lane. Mitchard’s writing has won or been nominated for the Shirley Jackson Award, the Orange Broadband Prize for Fiction, UK’s Talkabout Prize, and the Bram Stoker Award. A former daily newspaper reporter, Mitchard is a professor in the Master of Fine Arts program at Miami University of Ohio. She frequently writes for such publications as Glamour, O the Oprah Winfrey Magazine, Marie Claire, and Reader’s Digest. Her essays and short stories have been widely anthologized. She lives on Cape Cod with her family

Jacquelyn Mitchard was born in Chicago. Her first novel, The Deep End of the Ocean, was published in 1996, becoming the first selection of the Oprah Winfrey Book Club and a #1 New York Times bestseller. Nine other novels, four children’s books, and six young adult novels followed, including Two if By Sea, No Time to Wave Goodbye, Still Summer, All We Know of Heaven, and The Breakdown Lane. Mitchard’s writing has won or been nominated for the Shirley Jackson Award, the Orange Broadband Prize for Fiction, UK’s Talkabout Prize, and the Bram Stoker Award. A former daily newspaper reporter, Mitchard is a professor in the Master of Fine Arts program at Miami University of Ohio. She frequently writes for such publications as Glamour, O the Oprah Winfrey Magazine, Marie Claire, and Reader’s Digest. Her essays and short stories have been widely anthologized. She lives on Cape Cod with her family