Love That Moves the Sun illustrates the deep connection between the poet Vittoria Colonna and Michelangelo Buonarroti, while also painting a clear picture of the life and trials of Colonna. In this work of historical fiction, Linda Cardillo brings us into the life of this noble woman. We follow her path from girlhood and an arranged marriage designed to protect her family’s wealth and power all the way to the intellectual intimacy and mutual affection she shared with Michelangelo in Rome as he worked on The Last Judgement. Though written in the twenty-first century, the novel accurately defines the limitations placed on women in this time and culture simply by telling the story of Colonna’s life. The work is both a love story and a testimony to a woman who found a way to live a life of purpose between the lines of prejudice and restriction. We are thrilled to chat with Linda about her newest novel.

Amy M. Hawes: I read the book expecting it to be more about Michelangelo than Vittoria but was pleasantly surprised the opposite was true. The sculptor/painter is a universally famous figure but the poet is not. What drew you to her story?

Linda Cardillo: Like a number of old-world explorers, I discovered Vittoria Colonna while searching for something else. When my agent suggested that I consider writing historical fiction, my first thought was to look at Italian women artists as a potential story source. I was reading the catalog of an exhibition mounted by the National Museum of Women in the Arts and came across a scholarly article about the Renaissance women who influenced the art of the era as patrons. Vittoria was one of those women and immediately fascinated me. I had never heard of her before, which is true of so many women in history! I set out to learn more about her and definitely fell down a rabbit hole as I devoured everything I could find.

AMH: We know that arranged marriages were common throughout history to create alliances. However, we rarely get such an intimate portrayal of what it might have felt like to the woman involved. Often in fiction, the female either rages against or gives in to such a fate. It seems that Vittoria’s response might be what was most common – to be hopeful and make the best of it. What are your thoughts?

LC: From what I knew of Vittoria—her intelligence, her passion and her sense of mission—it made sense to me that she would approach her marriage with an expectation of the possibilities it afforded her rather than limitations. She had, after all, witnessed the marriages of her parents and grandparents, both of which were strong, happy unions. Her grandmother, Battista Sforza, was one of the “learned” women of the 15th century and held political power when her husband, Federico da Montefeltro, was away at war. Their court at Urbino was renowned for its enlightened culture. Her mother, Agnese da Montefeltro, had been educated in the same humanist tradition as Battista and took a similar role in her marriage to Fabrizio Colonna. Coming from such a background, Vittoria would have expected her marriage to be similarly fulfilling.

AMH: When she is still a girl, Vittoria is sent to Ischia to live with her future husband’s family. Costanza, the woman who raised her betrothed, changes the path of Colonna’s life forever. Why is their relationship so significant?

LC: Costanza d’Avalos was an extraordinary woman—beautiful, powerful and courageous— who defied restrictions and shaped not only her own narrative but the cultural, political and religious thought of her age. Widowed young, she took on the governance of Ischia, even taking up arms herself to defend her territory. She recognized the influence she could yield as the host of a glittering salon, bringing together artists, poets, and politicians. For Vittoria, growing up in such an environment provided her with a sense of confidence in the possibilities available to her in defining her own life. Costanza was a role model to Vittoria in her youth and a confidante in her later life.

AMH: Colonna describes seeing the Sistine Chapel ceiling for the first time and the connection she felt to the artist who painted it. I’m assuming this response was based on a real letter? Was it fate that she and Michelangelo would meet?

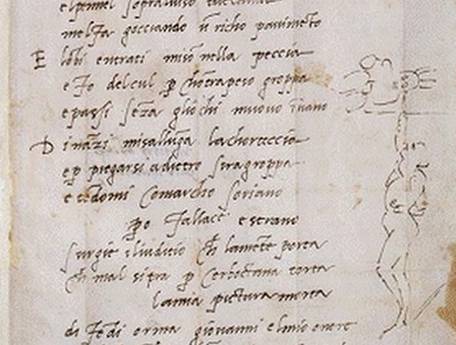

LC: This scene was not based on a real letter. Only a handful of the letters between Vittoria and Michelangelo remain, mainly because he ordered his biographer to destroy most of them. Lacking any historical record of what drew them together, I created the scene in the Sistine Chapel because I believe that by the time they met, both Vittoria and Michelangelo would have experienced one another’s art and been moved by it. Something extraordinarily compelling sprang to life between them, and that connection had its origins in the spiritual hunger conveyed in their art. I think a number of things put them on a path to one another: the power wielded by Pope Clement in drawing them both to Rome; their loneliness and isolation as revered figures; and their mutual search for transcendence from a world filled with pain.

LC: This scene was not based on a real letter. Only a handful of the letters between Vittoria and Michelangelo remain, mainly because he ordered his biographer to destroy most of them. Lacking any historical record of what drew them together, I created the scene in the Sistine Chapel because I believe that by the time they met, both Vittoria and Michelangelo would have experienced one another’s art and been moved by it. Something extraordinarily compelling sprang to life between them, and that connection had its origins in the spiritual hunger conveyed in their art. I think a number of things put them on a path to one another: the power wielded by Pope Clement in drawing them both to Rome; their loneliness and isolation as revered figures; and their mutual search for transcendence from a world filled with pain.

AMH: Their relationship was not a physical one but rather intellectual and emotional. Was it only social convention that kept them from that kind of intimacy or was it something else?

LC: Social convention certainly played a part, but Vittoria and Michelangelo were at points in their lives when physical passion was perhaps receding (or well hidden from both their contemporaries and history). Their eyes were on redemption. Keep in mind, also, that until he met Vittoria, Michelangelo’s lovers had been men.

AMH: Michelangelo is jealous of Vittoria’s connection to others. Why does he covet her? Is it a reflection of his brooding nature or specific to the poet?

LC: Michelangelo’s close relationships were few, intense and possessive, because they cost him a great deal. As Vittoria understands, “He closes himself off from all but a few of his closest friends, because each person he loves takes a part of him that is then no longer his. He believes that to protect his talent and to create requires solitude and concentration to the exclusion of anything else.” Having chosen to open himself to Vittoria’s love, he is afraid of losing her, and thus a part of himself, when she goes away.

AMH: What impact did the poet Colonna have on Michelangelo’s depiction of the Last Judgement? In other words, would it have turned out differently had she not been there?

LC: Vittoria’s role in the Last Judgement was profound. She interpreted the Gospel for Michelangelo and presented him with a vision that was uniquely her own.

AMH: Describe the process of creating this unique book of historical fiction. How much is historical, and how much is fiction?

LC: I am asked this question all the time! As a writer of historical fiction, I attempt to create an inner life for my characters based on what is known. I spent over three years researching the lives of Vittoria and Michelangelo, augmenting their biographies, letters and poems with an in-depth exploration of the history of the 16th century. It was a time of incredible turbulence and change—constant wars, religious dissent, and a cultural explosion in art and literature. I made two trips to Italy. I traveled first to Ischia, where the Castello d’Aragonese still exists and where I was able to walk in Vittoria’s footsteps. The second trip was to Rome and Florence, to absorb the environment of the Vatican, the Colonna palace and Michelangelo’s origins.

But I write fiction, not history. Where gaps exist in the documented record or scholars disagree, I weave imagined connections that foster the story while still reflecting what might be possible. To readers who may ask “What is true?” or “Did that actually happen?” I answer that I have followed the trajectory of what is known, with perhaps a slight adjustment of time now and then. But within the walls of the Castello d’Aragonese or the Convent of Santa Caterina or the house in the Macello dei Corvi, it is the heart that speaks the truth.

Linda Cardillo is an award-winning author who writes about the old country and the new, the tangle and embrace of family, and finding courage in the midst of loss. Hailed by Publishers Weekly as a “Fresh Face,” Linda has built a loyal following with her works of fiction—the novels Dancing on Sunday Afternoons, Across the Table, The Boat House Café, The Uneven Road, and Island Legacy, as well as novellas in the anthologies The Valentine Gift and A Mother’s Heart and the illustrated children’s book The Smallest Christmas Tree. Her newest book, Love That Moves the Sun, is a work of historical fiction set in the Italian Renaissance and based on the relationship between the poet Vittoria Colonna and the artist Michelangelo. Learn more at: //lindacardillo.com/

Linda Cardillo is an award-winning author who writes about the old country and the new, the tangle and embrace of family, and finding courage in the midst of loss. Hailed by Publishers Weekly as a “Fresh Face,” Linda has built a loyal following with her works of fiction—the novels Dancing on Sunday Afternoons, Across the Table, The Boat House Café, The Uneven Road, and Island Legacy, as well as novellas in the anthologies The Valentine Gift and A Mother’s Heart and the illustrated children’s book The Smallest Christmas Tree. Her newest book, Love That Moves the Sun, is a work of historical fiction set in the Italian Renaissance and based on the relationship between the poet Vittoria Colonna and the artist Michelangelo. Learn more at: //lindacardillo.com/